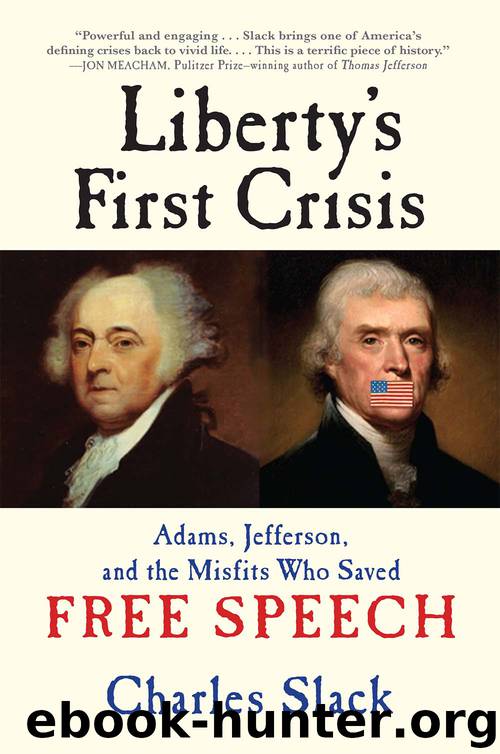

Liberty's First Crisis by Charles Slack

Author:Charles Slack

Language: ara, eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Published: 2015-02-20T20:43:49+00:00

Even as the Sedition Act shook James Madison from his Montpelier retirement, it provoked lesser-known Americans into reflecting on the meaning of freedom. Freedom, of course, had been at the forefront of the American mind since before the Revolutionary War. But now the conversation was changing from bold declarations against a ruling foreign power to subtler reflections on what liberty means in a functioning society, whether it can survive, and why objectionable voices must be permitted to speak. In January 1799, a Virginian named George Hay published An Essay on the Liberty of the Press. Hay, a thirty-four-year-old attorney with a private practice in Petersburg, south of Richmond, addressed his essay to the Republican printers of the United States.

It was divided into two parts, the first comprising a precise, detailed analysis of why he believed the Sedition Act was unconstitutional. Drawing a distinction between speech and action, Hay readily acknowledged the power of Congress to punish “insurrection or actual opposition” to government measures, “because the best laws would be of no avail, unless Congress possessed a power to punish those, who opposed their execution.”22 Hay then argued the case of constitutional limitations on federal power, pointing out that Congress had authority only over those areas specifically described in the Constitution. Thus even without the First Amendment, Congress lacked the specific authority to regulate speech and press, since those powers aren’t granted in the Constitution. But, of course, the First Amendment did exist, and this, in Hay’s view, eliminated any reasonable argument on the matter.

If his essay had ended with part one, the best that might be said of George Hay is that he added a logical if not terribly inspiring argument in favor of a strict interpretation of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. But the genius of Hay’s Essay on the Liberty of the Press lay in part two, where he anticipated and began to address such questions with a new American conception of liberty, one that needed some repressive test such as the Sedition Act in order to be fully galvanized. “The words, ‘freedom of the press,’ like most other words, have a meaning, a clear, precise, and definite meaning, which the times require, should be unequivocally ascertained,” Hay wrote. “That this has not been done before, is a wonderful and melancholy evidence of the imbecility of the human mind . . .”23

The Bill of Rights is perhaps the single most beautiful and vital document ever produced by a government—you can get goose bumps just thinking what it meant, against the long, grisly train of human tyranny through the ages, for a government to set about declaring the limits of its own power. Still, the Bill of Rights is not the source of our rights but a reflection of them, a mechanism for protecting them. This is of course what the Founders meant by unalienable rights being derived from nature or the Creator, as distinct from privileges, which can be granted (or revoked) by men. What George

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anarchism | Communism & Socialism |

| Conservatism & Liberalism | Democracy |

| Fascism | Libertarianism |

| Nationalism | Radicalism |

| Utopian |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19032)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12182)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8884)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6872)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6261)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5782)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5734)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5491)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5424)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5211)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5141)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5079)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4946)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4911)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4776)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4738)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4697)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4500)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4481)